Once, I went to a Van Gogh light show in Paris. Of course I’ve known Van Gogh’s work since childhood, but this show turned all those familiar static pieces into brilliant illuminations that drifted and swam all around me as I sat spellbound on the floor. This is what the whole world looks like in the Faroes. The clouds and waves and sunlight that I’ve always known were suddenly truly alive. They danced together to some frantic unheard song. One cloud hovered, another bloomed, and the last rolled over into oblivion. The sky behind them was the worn blue of a favorite pair of jeans, with a brighter patch telling me that the sun was coming soon, or maybe a squall, or maybe both in quick succession. The light constantly bounded between them all, slanting as it always does at high latitudes, and lending a golden warmth to the hues of the otherwise chilly islands. It felt like I could do was sit down and stare.

The approach

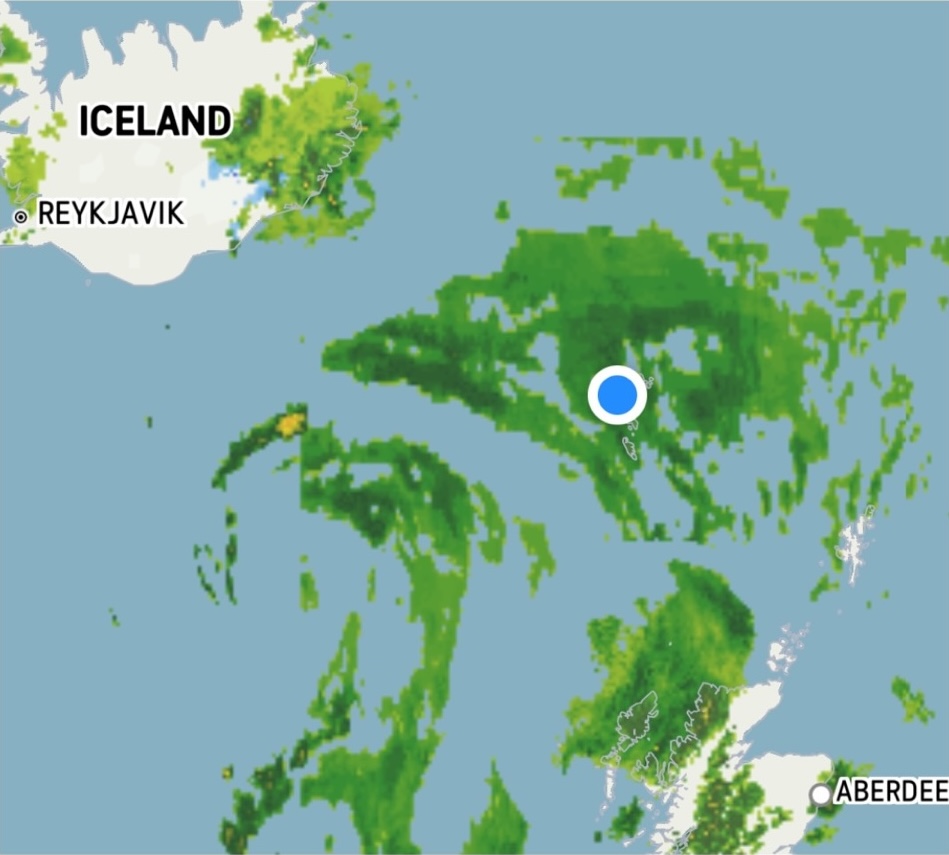

If there’s a really excellent time to visit a North Atlantic archipelago famous for its rain and wind, it’s during a post-tropical storm. The wind buffeted our plane on the descent into Vágar Airport, which made it particularly alarming when a cliff wall materialized at eye level from behind the clouds, closer to the plane than the ground was. Nevertheless a madwoman’s grin spread across my face. I’ve always loved thrill rides.

If neighboring Iceland is the land of fire and ice, then I nominate the Faroes as the islands of water. Water constantly falls from the sky, clings to the mountaintops, rolls down the hillsides, soaks into the moss, flows to the iron sea. The Faroe Islands are home to 55,000 people, 70,000 sheep (‘faroe’ meaning ‘sheep’), and probably more waterfalls than both those numbers combined. The first thing I did with my rental car was drive up to Múlafossur Waterfall, which is supposed to plunge into the sea, but when I stepped out to look at it, the squally weather turned the waterfall into a water-rise and my hair into a rat’s nest.

The sea is always just a few kilometers away when you’re in the Faroes, and if you’re in a car it’s more like just a few meters. For awhile the road hugged the coastline of Vágar island as it rambled on towards the hazy horizon, until the road decided it had other plans and zigged abruptly towards the water. Except it was not headed over a bridge, oh no. It slipped just underneath the skin of the island like a hypodermic needle, and then wormed its way under the seabed over to Streymoy island. The tunnel felt vulgar somehow, like I was privy to something that was never meant for human eyes.

Camping

If there’s a really excellent idea for what to do in the Faroe Islands during a post-tropical storm, it’s tent-camping. The swollen waterfall next to the Vestmanna campground absolutely roared like a jet engine all night long. As I crawled around my almost-new tent setting up my sleeping bag, I noticed that the floor felt like a waterbed – the mossy ground underneath was so impregnated with water that it was actually sloshing underneath me. I hoped that my waterproof tarp would live up to its name.

Camping is apparently a new hobby in the Faroes that arrived with the 21st century tourism wave. Locals have taken to it pretty well and have even set up some long-term campers, which I noticed were literally ratchet-strapped down to the Earth. I nervously re-tightened all my guylines. Only I and a solo Frenchman were brave enough to tent-camp that night, and the campground owner kindly offered to let us just sleep in the campground’s communal kitchen area1 if we needed to. Not particularly daunted by a bit of water, I pulled on my waterproofs and headed out to hike around in the nearby hills while the squalls and sunshine fought for control of the sky. It was near midsummer at 62 °N, where the sun barely dips below the horizon for a few hours each night. When I eventually burrowed into my 3-season sleeping bag, I had to pull my winter hat down over my eyes to shut out the perpetual twilight filtering in through my tent roof. In the early morning I woke perfectly dry inside my tent (woohoo!), but when I headed inside for coffee I found the Frenchman fast asleep on one of the kitchen’s couches. Tent camping really separates the ladies from the men.

Saksun

By happy accident I arrived at Saksun right when the tide was out, so I could walk through the fjord on sand flats all the way to the little black-sand beach. A gentle sloping path took me from the hamlet of Saksun, with its cute white church and sod-roofed barns, down to the water’s edge. A ewe and her two lambs accompanied me for awhile before dogletting and swimming out to a tiny island. Beaches on the Faroes are pretty rare and most of its coast is solid volcanic rock, so it was a treat to kick off my boots and dig my toes into the dark sand. The tide turned around before I did, and on the way back I had to wade through ankle-deep water that was rising by the minute. Luckily the sun made a warming appearance, but I still wore my winter cap and rain jacket because I’d already learned that the next squall would arrive soon.

Shepherd hike

“Camping? You thought that was a good idea?” asked the Faroese shepherd-slash-mountain-guide when I introduced myself to him and explained what I’d been doing on the islands. I thought this comment was a bit rich coming from a man wearing trousers, a sweater, and tennies while the rest of us were bundled up in hiking boots and waterproofs with our faces barely showing. “Well, when you’re young, you can sleep in a tent.”

The cheeky shepherd would be leading about ten of us on a hike up and over the scenic ridge between Tórshavn and Kirkjubøur. Whenever I find myself on a walking tour led by a fascinating guide, I bounce between two worlds: the photog club hanging out at the back of the pack and the front-row seats filled with teacher’s pets. The pea-soup fog followed us up and over the ridge, which gave me an opportunity to focus on the diminutive wind-swept plants just beneath my feet and the guide himself rather than trying to photograph the landscape.

“The oystercatcher is supposed to be our national bird, but every winter they leave for Scotland,” he quipped when the sound of wingbeats came to us through the mist. He followed no guideposts or trail. Huge rock cairns were scattered around, which our guide insisted were built by the local shepherds “because of boredom” rather than for navigation reasons. When we passed a decent-sized pond with a few big fish in it, he told us that he and his brother once carried live fry with them up to the pond to start this local population, just so they could do some fishing during the long days of shepherding. It’s possible he was pulling our legs, but how else would fish end up in a hilltop lake with no rivers coming in or out?

We were surrounded by signs of sheep, although the sheep themselves had not yet gone up the mountains for summer. Tufts of lost fur clung to the damp grass, and our guide picked one up and showed us how to pull the soft undercoat apart from the coarser overcoat. It had the slippery-cloud feel of a kitten’s belly, without the threat of a 20-claw surprise. It came to me last and I kept it. I worried the fleece between my thumb and forefinger deep inside my pocket, the same pocket that has held and lost all kinds of natural tresasures that I found and carried around with me for awhile: feathers, seashells, rodent bones plucked from owl pellets2. Eventually the treasures all fall back to Earth, often of their own accord, or when I remember I have no ownership over them and they belong outside where they can decay back into their elements. That ball of Faroese wool lived in my pocket for no less than three weeks before it disappeared, returning to nature somewhere on the streets of Germany. Perhaps it became the lining of a robin’s nest.

Towards the end of our still-misty hike, our shepherd guide joked that “you have to have a PhD to be a farmhand in the Faroes.” The Faroese have a nice philosophy: parents tell their kids to leave the country while they’re young because they can always come back, something like a Rumspringa for archipelagen fishers and shepherds. And come back they often do. His brother attained a PhD from Harvard before returning to shepherding. He himself left academia for the sheep after getting a Master’s degree abroad (and I was happy to hit him with my standard joke of “oh, so you’re smarter than me,” because he’d had the sense to quit while he was ahead). They just love being with the animals, he insisted – despite the obvious hardships.

On our way down the ridge into Kirkjubøur, we finally descended from the mist. We picked our way across the ruins of a 700-year-old church and other Viking ruins clinging to the shoreline. As I watched a wren hop around on the oceanside rocks and the clouds carressing the opposite island of Hestur, I thought I could see why people would choose this life over academia.

Driving

Driving on the islands means constantly moving through a vast landscape that is itself constantly moving. Once, I approached a nondescript cut in the hillside and for just a split second I was able to see deep into a slot canyon filled with a churning waterfall. Surprise jerked the wheel under my hands. Rarely do I speak aloud to myself, but the shock of the sight ripped a “nooo f*cking waeyy” out of my mouth, tinged with a deep-North accent I usually keep stashed away. You just never know what the next fold in the landscape will bring. A lost village, a misty fjord, a switchback over a sheep-laden mountain. Tunnels were an inevitability. Most of them were only wide enough for a single car and their dripping walls were left unfinished, like a pack of dwarves had just finished chiseling them out of the mountainsides.

The truest dark I ever saw that midsummer week was deep inside those tunnels. In the middle of the longest seabed ones, when I could only tell if I was going down or coming up by whether I need to brake or accelerate, colorful lights came out to say hello. In one tunnel they were sea-blue and purple, in another the white-red-blue of the Faroese flag. The largest and newest of the seafloor tunnels has a lit roundabout inside it, and I took a few lazy loops around the circle since I was the only car down there. Most of the roads were the same: brand-new, narrow, empty. I could park my car almost anywhere and stand on the centerline to take some photos with no fear of being hit.

Technically, you don’t need your own car to enjoy the islands. They’re pretty well-connected by buses and even commercial helicopters, but I’m actually talking about something else that many of us are probably uncomfortable with: hitchhiking. “Hitchhiking is so easy. And the crime rate here is 0.0000%,” a hostel owner would tell me on my final night, when I asked him the best way to get to the airport after I dropped my rental one day early to save some cash. “If you can’t get a ride, come back in here and I’ll drive you myself.” The point turned out to be moot because weather delayed my flight and I was able to catch a ride with another couple staying at the hostel. One day I did my part, though, when a backpacking Belgian couple approached me at a trailhead and asked for a ride back to town. I immediately agreed, which is the exact opposite of what I’d do in almost any other country on Earth. The Faroes just seem to attract a certain type of friendly and outdoorsy traveler, making the whole place feel like one big safe community.

Homestay in Leirvík

For all their well-traveled-ness, the Faroese are new enough to world of tourism that they haven’t quite figured out things like opening hours. One day when I visited a village’s lone cafe at noon, I found a note taped to the locked door that said “open 8-20” and listed a phone number to call for service. When I checked back 4 hours later, the handwritten note just said CLOSED.

So I was hardly surprised when I tried to check-in at my homestay in Leirvík and found the place abandoned. It took a few calls and about an hour before the owner showed up, but the sun was out and I had nowhere important to be so I just roamed around the town, admiring the cheerfully colored boathouses and Viking ruins. The only dinner options in town were a gas station’s “grocery store” and a bowling alley’s “restaurant.” My host later explained that “when people open restaurants here, they’re not thinking of you [tourists]. They’re thinking of what the Faroese like to eat: burgers, fish and chips, and pizza.” Fair enough, although that brings up new questions about Faroese palates. The biggest international chain I even saw on the Faroes was Bónus, the Icelandic grocery store whose bufoonish piggybank logo is among the greatest mascots ever made. Otherwise the place is wonderfully unsullied by the usual-suspect chains that have taken over the rest of Earth.

After my gas-station dinner, I took advantage of the endless evening light and walked up an old road along the coast, where I had a rather uncomfortable stand-off with a sheep. It was the closest thing to a road accident I had on the Faroes (not counting a few instances where I almost drove off the road because I was busy watching the landscape). Breakfast the next morning was a much tastier homecooked meal from my homestay host, including a local fish sausage that looked a lot like grey bologna and tasted like…well…puréed fish. I’m generally brave enough to try anything once – sometimes I just need to put a metric ton of mustard on top first.

Kallur Lighthouse, Kalsoy

The landscape was, at once, impossibly vast and impossibly restricted. I struggled to make sense of it. A 530-meter-tall fin of rock stabbed up from the sea, sloped down a kilometer-wide meadow, and then plunged back to the sea. The frozen green wave was dotted with tiny white commas that I knew to be far-off sheep. Yet the whole thing, from sea to cliff to slope to cliff and back to sea, all fit with in my field of vision without me having to turn my head. How could it be real?

There are many desire-paths leading through the meadow to the Kallur lighthouse, and they all began as desires of sheep. Just because there were lots of paths didn’t mean they were good paths, having been made by quadripeds with very sharp hooves who also like to poo while walking. I’d arrived at the trailhead with a public-bus-load of people, after a winding 40-minute drive past 4 isolated towns that each inhabited a concave seaside valley and were separated from each other by cliffs so steep they had to be tunneled through. We started off hiking as a pack, but we soon scattered across the web of sheep desires. Naturally I picked one higher up on the mountainside to get a better view. It was only as wide as a single boot, and as slippery as the midsummer’s day was long. Soon my pants were covered up to the knee in flecks of chocolate-colored…mud.

Some of the sheep apparently had daredevil desires, and their paths led right up to the cliff edges and along ridges high above the sea. The sea that hovers year-round at a balmy 4 degrees Celcius. At those temperatures, hypothermia sets in after just 4 minutes. I couldn’t quite stomach the most famous and very narrow saddleback path that led beyond the lighthouse itself, so I picked a slightly more reasonable-looking one to the east. It still felt like walking a pirate’s plank. Besides the narrow spine of slippery green earth holding me up, all I could see in any direction was the Atlantic.

On the way back, a gravestone right up along the opposite cliff edge caught my attention. I expected the stone to say something normal, maybe a tribute to the Vikings who’d lived here, or fishermen who’d been lost at sea, or tourists who had fallen off the cliff. The answer was d) none of the above. In fact it was a fake gravestone for James Bond, beacause (spoiler alert) it’s where Daniel Craig’s iteration had died in a recent movie. As I was inching along like a newborn giraffe, white-knuckling my hiking poles, I spotted lambs munching grass on the cliffside below me, apparently unbothered by the 300-meter drop just below us all. I looked down upon the backs of soaring seabirds and puffins. To my left rose that great fin of rock, taller than most skyscrapers. And out beyond rambled the silver silhouettes of the other Faroe islands, slumbering out in the mist.

Tórshavn

This shepherd-and-fisherman picture I’m painting might make the Faroes sound like a backwater, but I assure you they’re rolling in dough from the fishing industry and their ties to Denmark. Their currency, the króna, is tied to the Danish króna too. I understand foreign currencies best by how much it can get me rather than calculating how much it’s worth in “real” money. In the capital city Tórshavn, 10 króna got me 4 minutes of a hot campground shower and 20 kr. got a side of vegetables at the Irish pub, both sorely needed after hiking in the rain and surviving mostly on peanut butter sandwiches. A double whiskey was 80 kr. and 240 covered my campground fee, both useful for sleeping on the cold hard ground. What was it worth in Euro? Absolutely no idea. I can tell you, though, that the wayward Faroese islands are somehow cheaper to travel through than Denmark.

Tórshavn is definitely the cutest Nordic capital. The houses are modern and low and doing their best to protect the tiny garden trees from the howling wind. Right downtown there’s a tiny peninsula called Tinganes, which is one of the world’s oldest parliament seats and remains in use today. Sod-roofed houses and cafes are hunkered down next door, offering a nice respite from the squalls. By the fourth night of camping I’d learned that the sleeping weather would be pretty much the same every night, post-tropical storm or no (I ran into the Frenchman again, and by then he was just sleeping in his car). A twenty minte walk from the campground, up along the wild coast, was a free open-air museum showcasing some native plants and historic farmhouses half-buried in the turf. It’s no wonder a quarter of the population chooses to live in the capital.

End

You can tell how much I like a place by how many selfies I take, and in the Faroes I was a social media star – a windsewpt, pink-faced, and occasionally-dripping-with-a-mixture-of-sweat-and-rain social media star. It’s true I am a lover of nature, crazy weather, the sea, and the cold, so your mileage may vary. If you’re anything like me, though, I’d bet you’ll love the wild Faroes too.

Leave a comment