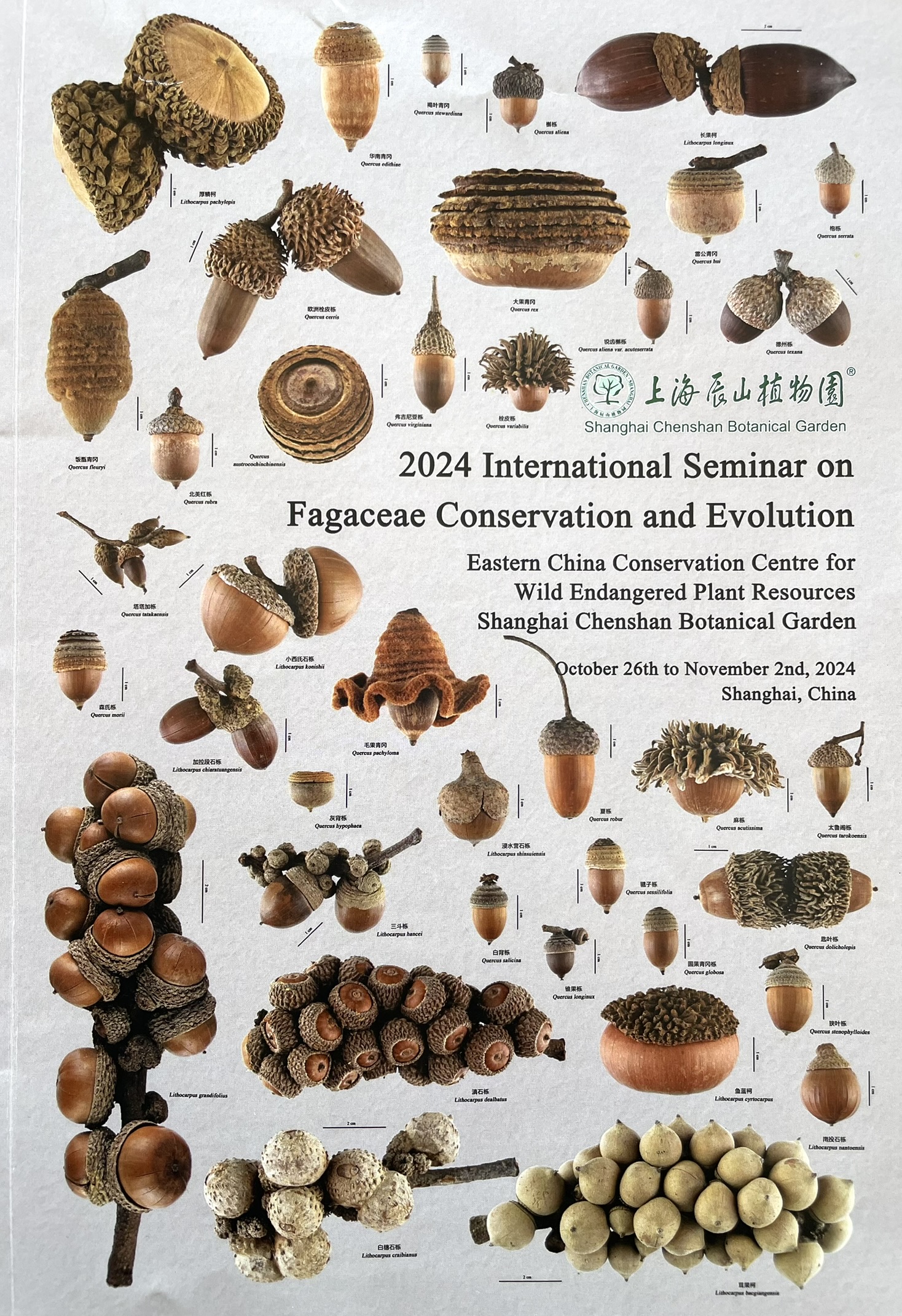

The Internet has existed for 41 years. By now, I think everyone knows what to do when you receive an unsolicited e-mail from a Chinese stranger who’s inviting you to come to some botanical garden in Shanghai and speak at a scientific seminar:1 mark it as Spam and delete it. However, no good story ever started with “mark it as Spam and delete it,” so I did the exact opposite. In the year 2024 A.D., knowing all the things I know about the Internet and Stranger Danger, I trusted this unknown person and accepted the offer at face value. Most people thought I was nuts, including my boss. It didn’t help that this so-called “2024 International Seminar on Fagaceae Conservation and Evolution” had no Internet presence at all when I searched for it (strike two). However, I was encouraged by the fact that this mysterious contact offered to sponsor my flight ticket and accomodations and a subsequent field trip to the southern Chinese mountains, since conference scams2 usually make you pay for all those things (and then never deliver). But how did I know this stranger was legit? How did I know they didn’t just want a kidney or worse?

I didn’t.

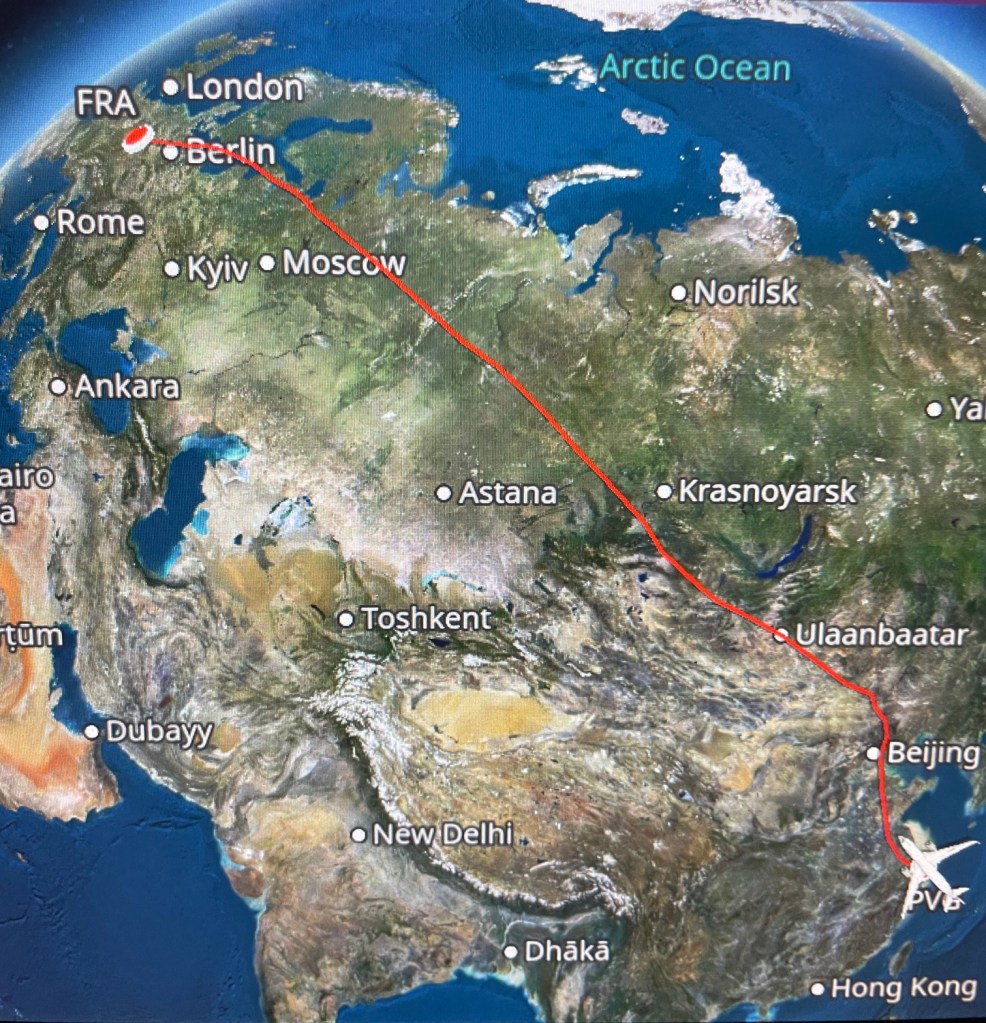

So it was with more than a little trepidation that I boarded the plane alone from Frankfurt to Shanghai. It helped that I was desperately curious about China, in a way I hadn’t been since the first time I visited Turkey (a country I visited before I even went to perennial European favourites like Italy or Scotland). It helped that some of the follow-up e-mails had cc’d researchers whose names I was familiar with, even if I didn’t know them personally. It helped that I was told I wouldn’t have to lift a finger in terms of logistics, which had always been a major blockade in my blue-sky plans to visit China. Still, as I flew over the entirety of Russia, The Unknown loomed black as a chasm before me, and all these “helpful facts” seemed to just keep falling into it.

The first moment of truth came when the plane touched down and I turned on my eSIM. China’s WiFi system uses a “Great Firewall” that blocks all the Western apps and websites I normally use to communicate, and I knew it was a real possibility that I would spend a week in The Unknown completely cut off from my people back home. After a breathless 60 seconds, the bars lit up and texts appeared. My little Millennial heart flooded with relief. My recovering-helicopter parents also seemed overjoyed. The second moment of truth came at the border, where I vaguely expected to be detained for filling out my paperwork incorrectly, but my expensive and difficult-to-obtain visa worked perfectly. The third moment came when I exited Customs into the ubiquitous gauntlet of hired drivers holding up name signs, and I looked around to see if anyone had actually shown up to collect me. Jackpot! Among a sea of Chinese hanji, I spotted my full name (middle name included) on a sign held by an older gentleman who had exactly 3 teeth. Hmm. Then I saw the two bright-eyed young students flanking him. They excitedly greeted me and patted my arms and told me to follow the driver to his sedan. Three for three successes; I guess nobody wanted my kidneys after all.

Any time I climb out of a plane and into a time zone that’s 1/3 of an Earth away from my previous one, I become punch-drunk. I can’t sleep while sitting upright, so I’d been awake for an unfortunate number of hours by the time the hired car peeled away from the airport. Brute curiosity was the only thing that helped me fight the hypnosis of the highway, and I watched as a kaleidoscope of urban forests unfolded across the landscape. Some forests were made of real trees, although they were strange ones: a patchwork quilt of saplings blanketed the countryside, each square hectare made up of a single species, which was different from all the patches around it, and none of the subtropical trees were familiar to my temperate eye. Other urban forests were stranger still, given that they were actually concrete: dozens of half-built pilons with rebar sticking out of their heads loomed over the sapling quilt, the predecessors to new highway overpasses that would soon soar over the land. What I didn’t see was the actual city of Shanghai. The airport was in a coastal Eastern suburb, and we looped South around the city for an hour until we reached the Chenshan Botanical Garden on the Western edge. We pulled up to the garden’s on-site lodging and the driver mumbled something that might have been English, then handed me his phone. My jetlagged brain somehow understood that I was supposed to talk into the phone, so I held it to my ear and said “Hello? The driver laughed and made a writing motion with his hand. Ah yes, a signature. See what I mean about punch-drunk?

I should mention at this point that the seminar was focused on a specific family of trees called the Fagaceae, which you’re probably familiar with since it includes beech, oak, and chestnut trees. What it doesn’t contain is the species I actually worked with during my PhD, which was also the thing I had been invited to China to talk about: Nothofagus pumilio, or “lenga beech,” which is a Patagonian tree from a related family called Nothofagaceae. The short version is that Nothofagus species were thought to be Fagaceae members until about 20 years ago, when DNA evidence suggested the two families had actually split way back when the supercontinent of Pangea broke apart. Today, Fagaceae trees mostly live in the Northern Hemisphere (including Europe, North America, and China), while Nothofagaceae ones almost exclusively live in the Southern. All this to say that, in a country and situation where I strongly felt like an outsider, I wasn’t sure whether the seminar organizers had read enough about my study species to know that it was an outsider too. During the journey to China, I’d nearly been able to forget about this little additional hiccup in light of other anxieties. Then I walked into the botanical garden lodge and met the chatty student helpers who were organizing check-in. Along with my room key, they handed me a few beautiful seminar souvenirs that had been printed with a motif containing China’s most diverse Fagaceae seeds — and no Nothofagaceae in sight. Uh oh.

Nothofagus pumilio in Argentina’s Patagonia

Left: Nothofagus pumilio forest, leaves and flower ; Right: The Fagaceae motif

While I would be reassured the next morning by my Chinese contact (and his supervisor) that I had been picked on purpose to single-handedly represent the Nothofagaceae family, my ongoing uncertainty and lack of sleep turned the first night’s welcome dinner into a pipe-dream. I found myself seated at a 10-foot-wide round table with some Chinese student helpers and the precious few other “young foreigners” who would be speaking at the conference: a friendly pair of students from South Korea with limited English and a Malaysian man who I would spend most of the week hanging out with. While we all stumbled through the awkwardness that is a bunch of young introverted scientists meeting for the first time in broken English, a perfectly coiffed 5′-tall woman carried in a couple steaming plates filled with curious things and placed them on a raised glass shelf at the center of the table. The dish closest to me contained thick slices of holey brown somethings swimming in caramel-colored sauce, and I stared at it for a long while, not even sure if it was vegetable or animal. I hadn’t come all the way to China to chicken out now, though, so I flailed with my chopsticks at an unwieldy slippery chunk and bit into it, relieved to find it was a vegetable like a water chestnut in a lightly sweet sauce. Only then did someone inform me it was lotus root. The hostess reappeared five minutes later with something else, and then something else, and the one-woman food parade didn’t stop for another two hours. Heaping bowls of odd vegetables and entire birds (with their heads still attached) somehow found space on the inner glass circle, which was apparently a turntable. One of the student helpers slowly pushed the disc around, and there was a flurry of chopsticks as everyone grabbed what they wanted before the dishes spun back out of reach. If no one was spinning, then you were free to inch your desired dish around until it was within chopsticking range, taking care to move slowly so others could take advantage of the conveyor. Being the only non-Asian at the table, I was hell-bent on wielding my chopsticks correctly, and was inordinately proud of myself two hours later that I’d tried all 20 delicious dishes without the help of a fork.

Food became a central theme to my stay in China, where there was always too much and it always came too often and it was almost always too delicious (and so much better than what the rest of the world considers “Chinese food”). By morning I was still full from dinner, but jetlag tricked me into thinking it was mealtime and I wandered downstairs to the employee canteen. Breakfast was a baffling buffet from which I chose a hard-boiled egg and a single bowl of rice porridge (read: plain rice with extra water?!?). I sprinkled a bit of white sugar on top for “flavor.” Not a single drop of coffee was to be found, which I might have expected from the country that literally invented tea, but it was still a rude awakening considering it was Sunday and I was slated to give a scientific presentation before noon.

Not knowing a single soul for thousands of kilometers in any direction, I walked alone into the seminar room. Finally: here was a space that felt familiar, a space I felt I belonged in. I was among the first to take my (labeled) seat and I watched as the attendees trickled in, most of them young locals. My mysterious Chinese contact took the stage, a fairly young and endearing fellow who was a research group leader at the botanical garden. The speeches began, and almost immediately our countless differences melted away. We became a hive mind that was interested only in seed experiments and oak speciation and forest conservation. At the first mid-morning break, the seminar caterers finally provided some coffee for us bean-addicted foreigners, although it tasted rather un-coffee-like. (The coffee situation hardly improved for the rest of the week, a daily sore point for I and the 15 other foreigners, chief among us a long-suffering Sicilian botanist.) By break time I was so tired I was literally becoming cross-eyed, so I downed three cups of the brew, happy to find that the caffeine worked regardless. My presentation came and went, as they do, accompanied by only a few waves of jitters. I stood with my research at my back and addressed the audience of 50. Closest to me sat two rows of invited speakers: the first held the professor-types and the second held the early-career professionals, including a French artist who’d been contracted to make a piece about the seminar and, judging by her intense listening-expression, clearly was not a scientist. Behind that rose a tiny wave of attendees that reached up to the rafters. Most were listening intently, but a few were dozing, which was understandable considering that it was a Sunday3 and I was objectively speaking English too quickly. While English is currently the lingua franca of Science, I routinely receive complaints about the pace of my mother-tongue speech. I realized I should have cut half the material from the lecture so I could have spoken slower and helped people understand better, but when I arrived to the group dinner that night, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that many people had understood perfectly well and were filled to bursting with questions for me.

I’ll generalize a bit here, and say that the Chinese people I met were absolutely some of the kindest and friendliest people I have encountered. I say this after having visited some of the “known friendliest countries” like Canada, Thailand, and Australia, and the “happiest” Nordic countries. Normally I’m a bit of a wallflower at conferences, but in Shanghai this wasn’t possible and I was constantly approached by students who peppered me with questions about my work and life, always speaking through huge smiles. I thanked them for this attention by being a source of entertainment at dinner. They watched me flail with my chopsticks and try all of the unrecognizable foods, asking me to guess what I thought the ingredients were. It only took me three guesses to figure out the jellyfish. Fortunately they pointed out the cow’s stomach before I put any of it into my human stomach. They were so genuine and generous – every mealtime, the seminar host himself would personally seek me out, because he knew that I have a problem with gluten, and he would enlist one of my willing tablemates to vet every dish I tried to eat and make sure it was safe. I had never received such treatment at a scientific event before, where I’m usually left to fend for myself.

Lotus root, jellyfish, and some kind of plant-based dessert

Our 2-day seminar ended already the next day at noon, and our playtime began after lunch. Our first order of fun was to actually tour the botanical garden itself. We hadn’t seen much of it yet because we’d been sequestered at one edge of the huge park to do our weird science stuff. We climbed aboard a toy train and got hauled over to the public-facing part of the park, which had only been established 14 years before. We wandered around impeccably landscaped outdoor subtopical gardens, through the flooded guts of an old quarry complete with a waterfall, and inside twin oblong glass greenhouses that looked like the backs of scaled dragons and were dedicated to the wet and arid tropics, respectively. As I was poking a cactus to see how sharp it was, I noticed the seminar’s hired photographer lurking behind a tree, taking candid shots of me. I changed tacks and tried to look like a professional scientist for a few minutes, and happily got some very respectable photos out of it. Our final stop was to a recently-planted Fagaceae garden. All of us grown scientists, aged 20 to 60, started pawing through the grass underneath the trees, hunting for acorns. While we Western Hemispherians probably think we’re familiar with acorns — round, brown, kind of boring — these were something else entirely. Some had spiky tops, like one of the gelled hairstyles my brother wore in the 90s. Others grew in fist-like clusters, their dozens of fingernail-sized seeds burnished to a high shine. An alarming number of the seeds disappeared into pockets and backpacks, certainly not to be squirreled back to everyone’s countries of origin. Then it was time to say goodbye to half of our crew, which I lamented enormously since it included most of the wonderful students I’d met, while the rest of us headed for the airport.

Accepting an invitation from a complete stranger to speak at a Shanghai conference after I published one single scientific article was crazy. It was also nothing compared to Part 2 of my Chinese adventure: a 5-day sponsored field trip to the tropical mountains, to look at trees with a bunch of botany nerds.

(Stay tuned for Part 2.)

Leave a comment