In theory we should have been able to see Mt Fuji during the bus ride up the valley from Tokyo, but the southern horizon remained obscured by a steel-grey curtain of clouds until nightfall. Was it Buddha’s Curse, or was it because Fuji is a notoriously shy mountain that only occasionally shows its face? The world may never know. The snow cover increased alarmingly as our bus climbed higher, and by the time we made it to the town of Fuji Yoshida it was fully winter again and there was a solid 5 inches covering the ground, which in today’s climate-changed world isn’t something to sneeze at. We had a very slushy walk (and a very slushy wheely-bag experience, in Yasin’s case, during which I finally felt vindicated for schlepping a backpack) to the guesthouse to dump our gear, before we continued uphill to where the edge of town met the forested foot of the volcano.

Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen Shrine has enshrined the volcanic deity of Mt. Fuji for millennia, and it also marks the start of the summer-only pilgrimage path all the way up the mountain. The closer we got to the shrine the taller the trees got, until they towered above us like the giants of Lothlórien. Half the trees were cedars that wore shredded coats of blood-red bark, and the others were cypress so chunky it would have taken four humans to hug a single one (we know because we tried it). At opposite ends of the majestic snow-covered path stood two enormous torii gates which mark the symbolic division between the physical world and the divine. One was silver and the other vermilion, both of them looming above our heads but still dwarfed by the trees. Being two forest biologists who are constantly distracted by life, our path between the gates was anything but straight. The majestic snow-capped buildings of the shrine encircled two monstrous cypress trees that have each witnessed over 1,000 years of life on Earth. One had been partially destroyed in a fire some time ago, and some industrious humans had literally just bolted some fresh rectangular swaths of bark onto the damaged side, like they’d been re-turfing a lawn. The entire complex itself had a certain quiet grandeur as it slumbered there in the ancient woodland, completely self-assured of its place in the world and knowing that even if it burned down, the humans would just patch it right back up again. Out of the dozens of shrines we visited in Japan, I think that one was my favorite.

We left the shrine at the imperfect time: every single cafe between the volcano and city center was already closed. We finally found one adjacent to the train station, and although it looked abandoned from the outside, a quick glance through the frosted window revealed an orange glow and the silhouette of a patron sitting at the bar. As we walked in, it struck me that traditional Japanese cafes were built to the scale of their owners. This one belonged to a wizened old woman who looked at least 75 and by Western standards probably would have been 10 years retired and wrapped in a Mumu at home, but instead she was still on her feet behind the bar at 6 p.m. catering to two gentlemen who were sitting apart, one reading manga and the other watching a sumo match on TV. Smoke from their two cigarettes curled toward the ceiling, further darkening paint that was already sepia-toned from decades of tobacco use. That the ceiling had a fairly normal height underscored how the furniture all stood at two-thirds scale, including a bar that rested at a comfy level for its sub-5-foot owner and twin china cabinets behind her that were stuffed with dozens of mismatched mugs. Our grasp of the Japanese language matched her understanding of English (≈nonexistent), so we just pantomimed that we wanted coffee. She began the Japanese ritual: grinding fresh beans and dumping them into pour-overs, slowly and methodically adding water by hand until the brewing process was complete. Meanwhile we had folded ourselves into a pair of diminutive chairs near a darkened window. I was having a decidedly easier time than six-foot-tall Yasin, but even so my five-six knees were wedged tightly against the underside of the table. The owner extracted herself from behind the bar, moving with all the speed of a sloth but with surprising surefootedness and strength as she served us. We slipped into a cold-and-exhausted TV coma, sipping our delicious coffee while zoning out to juvenile sumo and then a unicorn-colored adult news broadcast inexplicably shown on the same channel. When we finally stood to leave, the old woman took in Yasin’s unfolded height and delightedly exclaimed basukettoboru!, the Japanese loanword meaning, obviously, basketball. Some dumb jokes are clearly cross-cultural. We smiled and bowed in the traditional Japanese gesture of thanks, then dove back out into the night.

Our accommodations for the week were split between Western-style rooms, which contained raised box-spring mattresses, and Japanese-style, with thin futon mattresses laid directly on a tatami (woven-mat) floor. In Fuji Yoshida we had a Japanese-style room in an old traditional house with walls so thin that, if you were in our room on the upper floor, you could have heard a mouse’s fart all the way from the ground-floor kitchen. It was my first experience with a tatami mattress and I had a restless night, but in fairness it was probably because I had set an alarm to wake up near dawn and, based on prior experience, I was terrified I’d sleep through it. To those who know me, my goal of waking up at dawn is probably alarming, but I had a good reason: we’d heard from a few people that Fuji is most likely to show itself very early in the morning. I panic-woke every few hours to lift the curtain next to my head and check the black sky for clouds. When the sun finally arrived I dragged myself upright, but the neighbor’s house stood directly between our window and Fuji, so my results were inconclusive. I tugged on my boots and stumbled outside into the frozen world. Like a mirage the unveiled volcano hovered at the end of our driveway. I was pulled towards it like a moth to flame, literally walking up the road. Eventually the cold reminded me that I had left the house in my pajamas and without a jacket. Or Yasin.

Scared that the clouds would descend again at any moment, I changed within five minutes and badgered Yasin out the door. Counterintuitively we put our backs to the blazing white volcano and walked away down the street to the famous Honcho Street vantage point, where the street aligns perfectly with Fuji’s bulk. The point is such a tourist draw that the city has employed a few exasperated traffic wardens to stand there and herd the badly-behaved tourists around whenever they ignore the traffic signals. Sadly we were included in that statistic, but only the first time we crossed the street, and only because we couldn’t actually locate the small pedestrian lights. We lasted an impressive 8 traffic-light cycles out in the cold, one of us crossing the street and then crossing back like we were solo Beatles, only to switch phones and repeat. Finally we succumbed to the morning chill and sat down in the sun outside the kitty-corner cafe, looking wistfully through the window at the lone barista, who pointedly ignored us until precisely 8:00 a.m.

After a soul-warming indoor sunbath-and-coffee experience we aimed our feet towards a famous hillside pagoda and accidentally stumbled into my second-favorite shrine of the trip instead: Fujisan Simomiya Omuro Sengen Jinja. It wasn’t technically open yet so it was entirely deserted besides a few employees in traditional dress, who were kind enough to give us some early goshuin anyways. I’m not sure why that shrine was my second-favorite. Maybe it was the lingering snow cover, or the unique decoration, complete with tiny horse statues and wooden bridges affixed to a tiny rock “island.” Maybe it was because we hadn’t intended to go there and so it felt like a discovery. Maybe it was the tranquil juxtaposition against the bustling hillside pagoda that we visited next, which is arguably one of the most-photographed places in all of Japan. In fairness, Chureito Pagoda was undeniably gorgeous and worth the stop, even if I was mildly upsetted by the “Beware the monkeys!” signs that made me excited to see wild monkeys and then sad when I didn’t see a single one. Anyways, our timing for the morning was perfect: by the time we began our bus journey south around the base of Fuji towards Mishima, where we would board a Shinkansen train, the volcano had enshrouded itself and we never saw it again. Perhaps our privileged morning volcano viewing was a sign that the Buddha had finally forgiven us.

Kyoto

Shinkansen means “land plane” in Japanese, or so I assume, because that’s the only description that fits. The maglev bullet trains max out at 500 kilometers an hour, which is exactly as terrifying and incredible as it sounds when the ground sits just below your feet. Within two hours of boarding the train in Mishima we had arrived in Kyoto. I had been way too excited by the scenes of pastoral Japan zooming past the window to even attempt my premeditated nap, or get up to check out the restaurant car. I guess I’ll sleep and eat when I’m dead.

Kyoto is one of the most popular historic cities in Japan, with a living geisha district and traditional teahouses and entire walking paths that are lined with ancient religious sites. Most of its hotels are traditional ryokan-style, too: historic black-and-tan affairs with all the bells and whistles, like paper doors and tatami floors. In other words, Kyoto is a tourist magnet. While Tokyo had been so enormous that the tourists seemed to scatter across it like tiny pollen grains blown into a meadow, and Fuji Yoshida had been a nearly-deserted winter wonderland, Kyoto felt like it heaved with foreigners. Yet I let myself be charmed by Kyoto anyways, if only because it was hard to resist. Classical music was piped onto the city sidewalks through loudspeakers. Adorable dessert shops selling cloud-shaped cakes and delicious black-sesame-flavored custard reeled us in. Within the first hour I had bought a handmade owl-faced ring with purple eyes that reminded me of Mr. President, the Tokyo owl who’d stolen part of my soul, and street shopping is always a sure sign that I like a place.

Modern meets ancient on the streets of Kyoto, and both seem remarkably content to let the other breathe. For example, Japanese shōtengai shopping districts are essentially just a bunch of open-air alleys protected by a glass roof and are therefore neither truly indoors nor out. We dove into one that was occupied by a thousand tiny shops selling phones and new kimonos and other things I couldn’t even begin to identify. Then one of the doorways in the middle of the covered arcade abruptly yawned open to reveal an outdoor cul-de-sac, in the center of which stood an ancient shrine. It seemed they had literally built the streets, and then shōtengai, around it. Meanwhile, a few streets over in the district of Gion, dark brown M.C. Escher-like geisha neighborhoods fold inwards onto themselves in a series of crooked alleys and staircases. The self-contained worlds are surrounded on all sides by wide straight thoroughfares that are filled to the brim with shiny cars and modern department stores. Two worlds, both very much alive.

Desperate for some quiet and looking for more goshuin (to which I was already addicted), the next morning I led us to the very edge of town where the Philosopher’s Path begins. Many years prior, a philosophy professor had walked the same path to work while meditating every day. Today the path is an Established Destination that’s lined with shrines and artisan shops and cafes. Before we even reached the start of the path we let ourselves be caught by a tiny man who reeled us into his cafe, which was overflowing with antique cameras and Japanese typewriters covered in thousands of ideograms. His wife somehow managed to talk us into getting a few slices of matcha cake despite not using a single word of English. Before they could silently sell us an old Nikon camera too, we parted ways with a bow and walked up to the wide hillside canal that marked the beginning of the path. A riot of plum-blossoms greeted us on that cloudless day and its perfume cast a spell over us as we lazily migrated from coffeehouse to shop to shrine and back again, all the way down the canal.

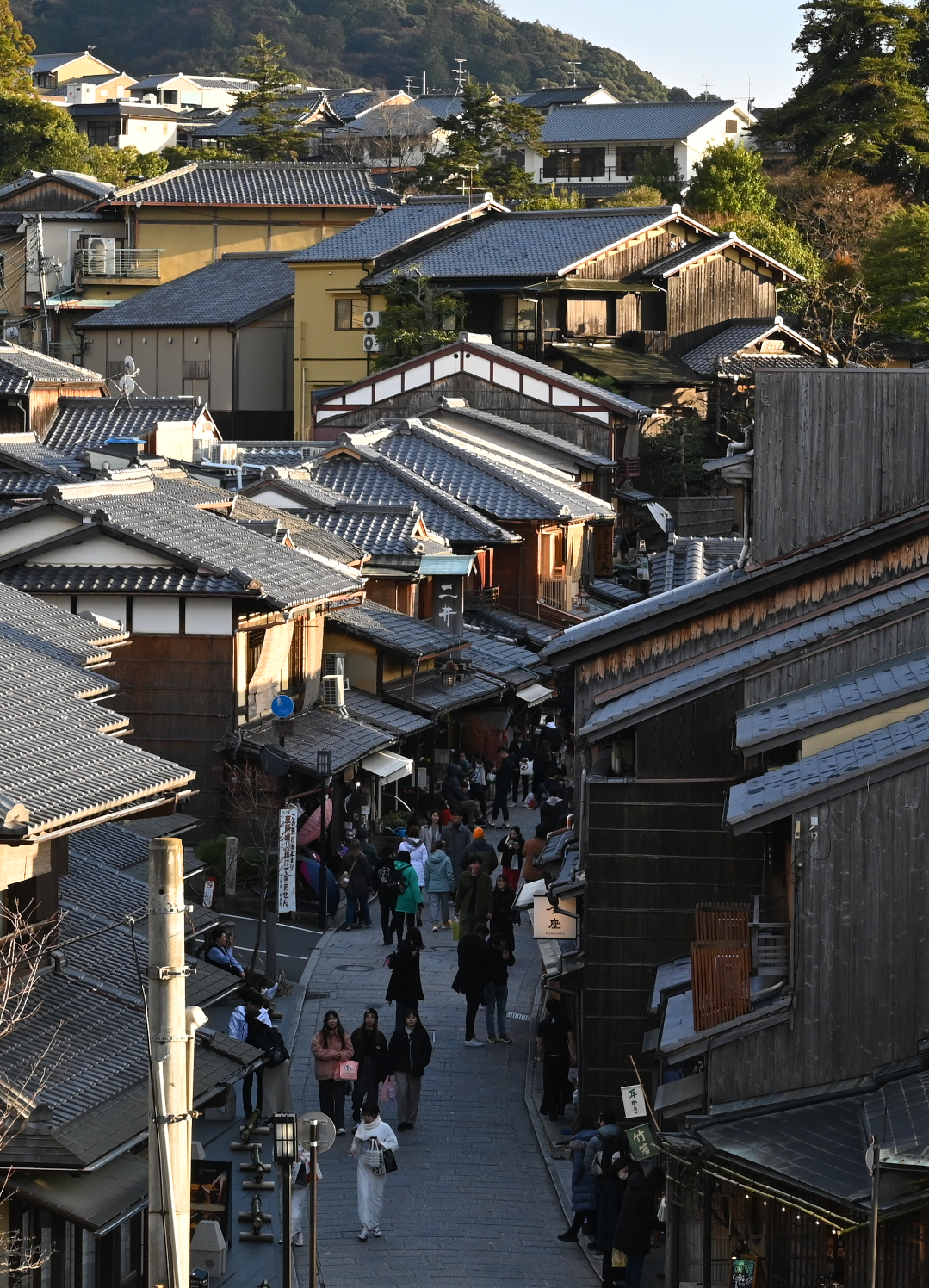

I’m a firm believer in letting myself be surprised by a destination rather than doing too much research beforehand, which can have either disastrous or amazing results depending on whether I happen to miss or find the highlights. Fortunately we accidentally found Ninenzaka, one of the more beautiful and famous historic districts, during our sunset journey to the hilltop temple of Kiyomizu-dera. Ninenzaka is a chocolate-brown wooden labyrinth that clings to Kyoto’s eastern foothills. Stuffed with shops selling Studio Ghibli merch and other local souvenirs, it was a perfect red-carpet entrance up to the temple. Ninenzaka was even populated by mild-mannered youths dressed up in rented kimono, all of them giggling and posing along the street. In other countries, it’s mostly foreign tourists who wear traditional local outfits and walk around having photo shoots (see: Oktoberfest), but in Japan I was delighted to overwhelmingly see local adults of all genders doing it.

We reached the temple just as the sun’s lingering rays turned the world to gold. This had an alarming effect on the chocolate hue of Ninenzaka, not to mention the magenta plum blossoms and the temple’s blaze-orange paint, all of which took on an ethereal glow. Huge modern art installations were scattered around the temple complex, including a spacesuit-wearing cat and a gigantic inflatable doll complete with a creepy speaker voice. It all combined to push my sense of disbelief into outer space. We came to rest next to a towering pagoda and I squinted through the dying golden rays out over the city of Kyoto, which rambled in a blue-grey haze to a mirroring set of hills on the city’s Western side.

Eventually we followed the beckoning of the sinking sun and headed west towards our local ryokan home, surrendering early to the falling night because by then Yasin had been gripped by a nasty cough. (Was it a predictable outcome from traveling and being surrounded by thousands of other people in springtime, or was it Buddha’s Curse? In any case, I somehow managed to avoid catching the bug). As we walked through the darkening streets of Gion towards a gluten-free-and-vegan ramen dinner spot, we finally saw a few beautiful young geisha walking around. Impeccably dressed and with every exposed inch of their skin painted bone-white except for the traditional bare patches on the backs of their necks, they invariably turned heads. I snuck glances at them too, but my attention was truly captured by a single older geisha dressed in jade who sat motionless at a bus stop. Her distinguished posture spoke of a woman whose behaviors are so ingrained that she no longer needed to strive for elegance; she just was. While she sat there in the most normal of situations, she exuded an air similar to the temple we’d toured at the base of Mt. Fuji: a timeless assuredness of her place in the world, even as that world changed around her. I stared transfixed until we rounded the corner, when both she and I disappeared into the modern-ancient streets of Kyoto.

Loved reading this blog- parts 1&2. Can’t wait for 3!

LikeLike