The scenic route to Buenos Aires

I am crammed in a tour van with 19 Germans, hurtling through the ink-black Argentinian steppe. Everyone tries to sleep, but every few minutes we are rudely jostled awake as the van skids over yet another washboard and into yet another pothole in the unpaved highway. I’ve never been skilled at sleeping while sitting, so after a few failed attempts I stare out the window into the night, wondering what the hell I’ve gotten myself into this time.

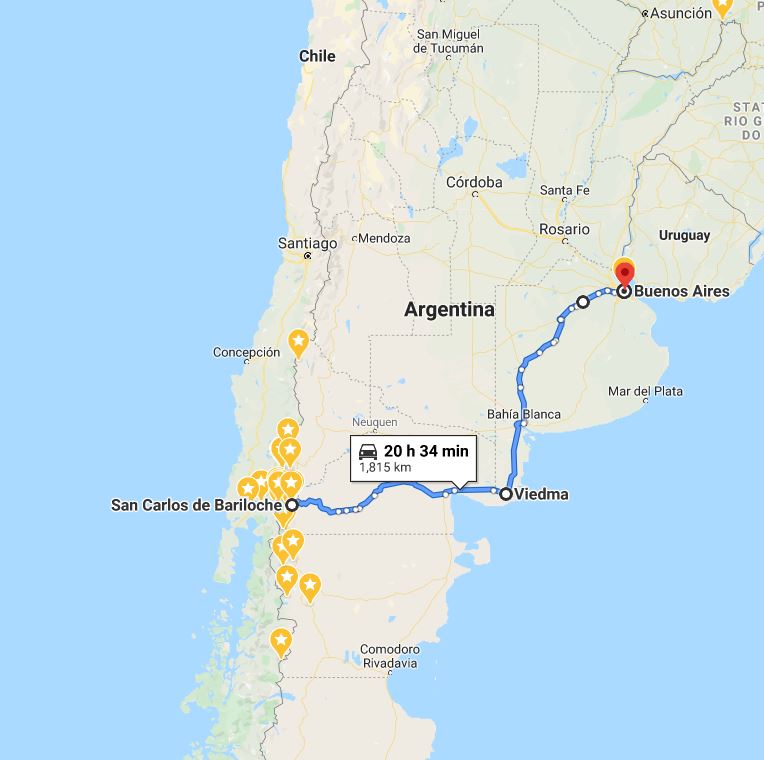

Fewer than twelve hours earlier, I had received an excited call from my supervisor. She said the local German consulate had chartered a microbus leaving Bariloche for Buenos Aires at 6 pm (in four hours) and that we had one hour to decide whether we wanted to be on it. We had misgivings; we didn’t have a plane ticket overseas yet, had no place to stay in Buenos Aires, and didn’t really want to leave our comfortable garden apartment in Bariloche either. But a one-minute discussion was all it took for us to commit, recognizing with rare clarity that this was finally our chance. The day before, all domestic flights, including the few Aerolineas rescue flights that had been operating, had been grounded for the next two weeks. The German and US embassies had both suggested that the only way to reach Buenos Aires, over 1700 kilometers away, was to hire a taxi – for over 1000 Euro.

From the moment we arrive at Bariloche’s German consulate and a small group of travelers begins to assemble around us, we are the talk of the town. People lean out their apartment windows to watch us; they stare us down from the opposite sidewalk. At least one of them calls the cops on us for “breaking quarantine.” No fewer than three different police crews stop, ask to see our passports, and tell us to stand farther apart. The last finally sets up a traffic stop right next to us, maybe on purpose, both to keep an eye on us and to head off the dozens of other police patrols that drive by. Curfew falls with the night, and the streets empty. It takes three hours longer than anticipated just to obtain the necessary permits to drive on the roads.

But it’s fine. It feels like all I do these days is wait.

I have never seen so many Germans in one place in Argentina. German travelers tend to roam as lone wolves or in small packs, and rarely congregate in such a manner. There is a family and a friend group, a young couple and an old, some singletons who flit from one group to the next with an easy grace learned in hostels and bars across the world. There’s a man with his bicycle, his trip north from Ushuaia truncated less than halfway through. All of them appear reserved and resolute, more collectively patient than I think I’ve ever seen a group of Germans be. There is relief in the air – we have finally been remembered and saved – mingled with disappointment, each of us mourning the loss of our planned travels (and work). I think many of us had held out hope that the situation would change and we would be allowed to continue on, but the moment we step on the bus, we will permanently kiss those dreams goodbye.

At 10 pm on March 30th, ten days after quarantine began, we finally leave Bariloche. We each clutch a flimsy scrap of paper that certifies our good health upon leaving Bariloche (verified by a forehead temperature scan). Neuquén, the province immediately to the north, has refused to let us pass through its borders, so when we reach the village of Dina Huapi we must leave Ruta 40 and careen off onto a dirt highway headed east towards the Atlantic coast – a detour that will cost us three hours.

As the night deepens, the trip becomes a fever dream. My increasingly exhausted mind starts seeing shapes in the headlight-illuminated steppe grasses flickering past the window. Pulsating blue lights appear every hour or so, marking police stops where the van halts for twenty minutes and masked silhouettes circle slowly around us. One or two board the vehicle, their exhausted eyes meeting ours, and collect our passports. Mine always stands out, a navy sliver in a stack of maroon. Sometimes there are questions, and we let our volunteer spokesperson tell white lies for us all: yes, all of us do have plane tickets leaving from Buenos Aires tomorrow. I am lost in a sea of half-understood Spanish and German. We are eventually waved on, occasionally escorted by a police truck through whichever hamlet we are nearest to. I squirm in my seat, desperate to find comfort in this wretched position. I manage to fitfully doze only a handful of times. The last time I when jerk awake from a shadow-dream, the sky is on fire. Fluorescent orange fills the entire inverted bowl of the sky, and just like that I know we are close to the sea.

Abandoning all hope of sleep, I resume my watch on the brightening steppe. We were only locked in the Bariloche house for ten days, but watching these novel ranchlands slide past us now is almost emotionally overwhelming. Families of emu-like ñandú stand in the scrub, one black-necked adult keeping watch over the young ones grazing for breakfast. Islands of red and pink dot the roadside at regular intervals: sun-baked shrines for Gauchito Gil, the unique Argentine “saint” who is charged with protecting all travelers who pass. We pass a neverending string of towns, all invariably marked by four things: an enormous welcome sign facing one direction, the entrance to a dirt road, a gas station, then an enormous welcome sign facing the other direction. I begin to suspect I’m hallucinating when I see two tiny burrowing owls perched on the northbound sign to the town of Hilario Ascasubi, followed quickly by a house-sized metal onion hovering above the southbound.

Around hour 18, I start immediately dreaming every time I close my eyes, except I skip the step where I actually fall asleep. During one such episode I try to scratch my nose and miss, because my hand can’t quite remember where my nose actually is. My ribcage aches from being upright so long; this van and these seats were not meant for transcontinental journeys.

Around hour 22, night falls again. By this point, my travel companions are sporting some truly unique hairstyles, largely of the “rat’s nest” persuasion. I vaguely realize that all of this will be hilarious some day, but it is not this day.

Finally, 25 hours after we left Bariloche, after careening all over a deserted Buenos Aires dropping people off, I make it to my temporary student apartment, and slide sideways into a dreamless sleep.

Now here I am, stranded in Buenos Aires instead of the sticks. But at least I am at the center of the action, and in the best position to eventually make my escape. I live in a six-room student apartment, built with such European architectural flair that I forget where I am until my skin is tickled by a subtropical breeze. A man-made canyon looms outside my window, beige skyrises parenthesizing a few low slum houses and two towering bottlebrush palm trees. Although I miss the garden, I am fortunate that the blazing sun tracks an arc through my window for eight hours a day.

My roommates are two French and two German students. We each largely hibernate in our rooms during the day, self-medicating with Netflix and solitude, and only occasionally pass each other during kitchen pilgrimages for snacks. But when night falls, we often gather to drink and laugh and play card games, listening from our third-story cave as the city periodically claps for the heroes who are pulling us through this pandemic. The police are less vigilant here, and I revel in being able to walk down the street to the grocery stores. I try my best to forget that the ocean is only a mile away, and that I cannot walk along its shores.

It is already a strange new world.